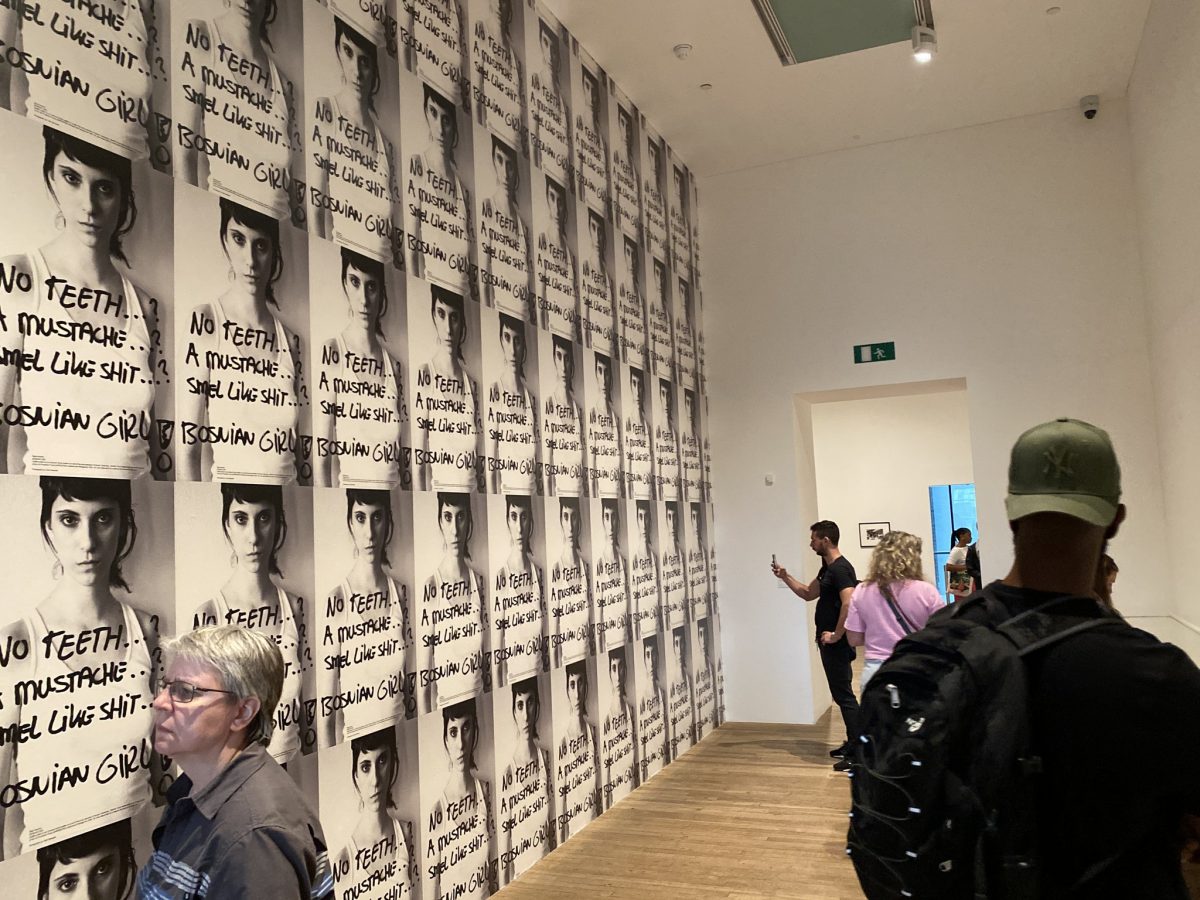

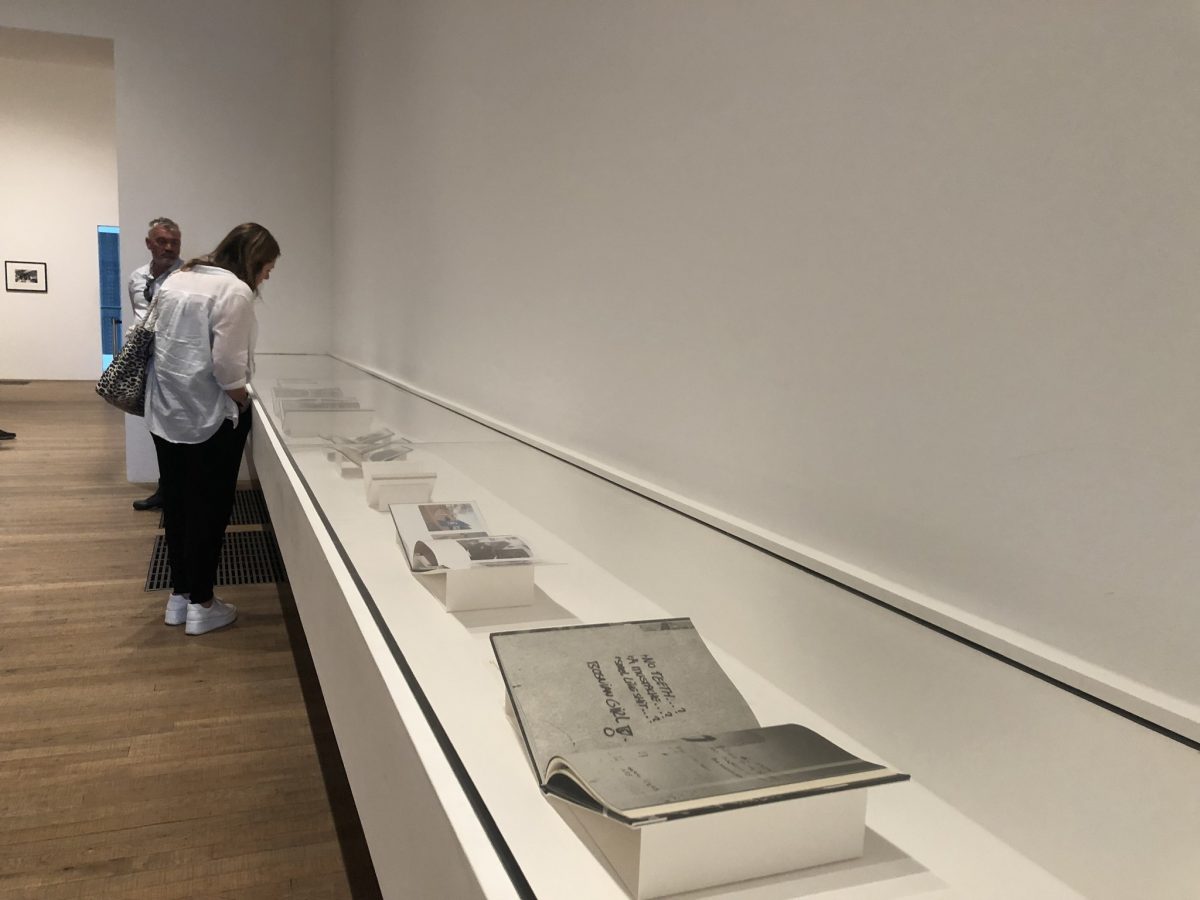

Monography “Srebrenica” by Tarik Samarah and the artwork “Bosnian Girl” by Šejla Kamerić are currently displayed in London’s Tate Modern gallery. The exhibited works are located in the central exhibition space, on the second floor, as part of the cycle “Artist and Society”, which represents a story about the ways in which artists and art deal with the social reality.

Bosnian Girl at Tate Modern

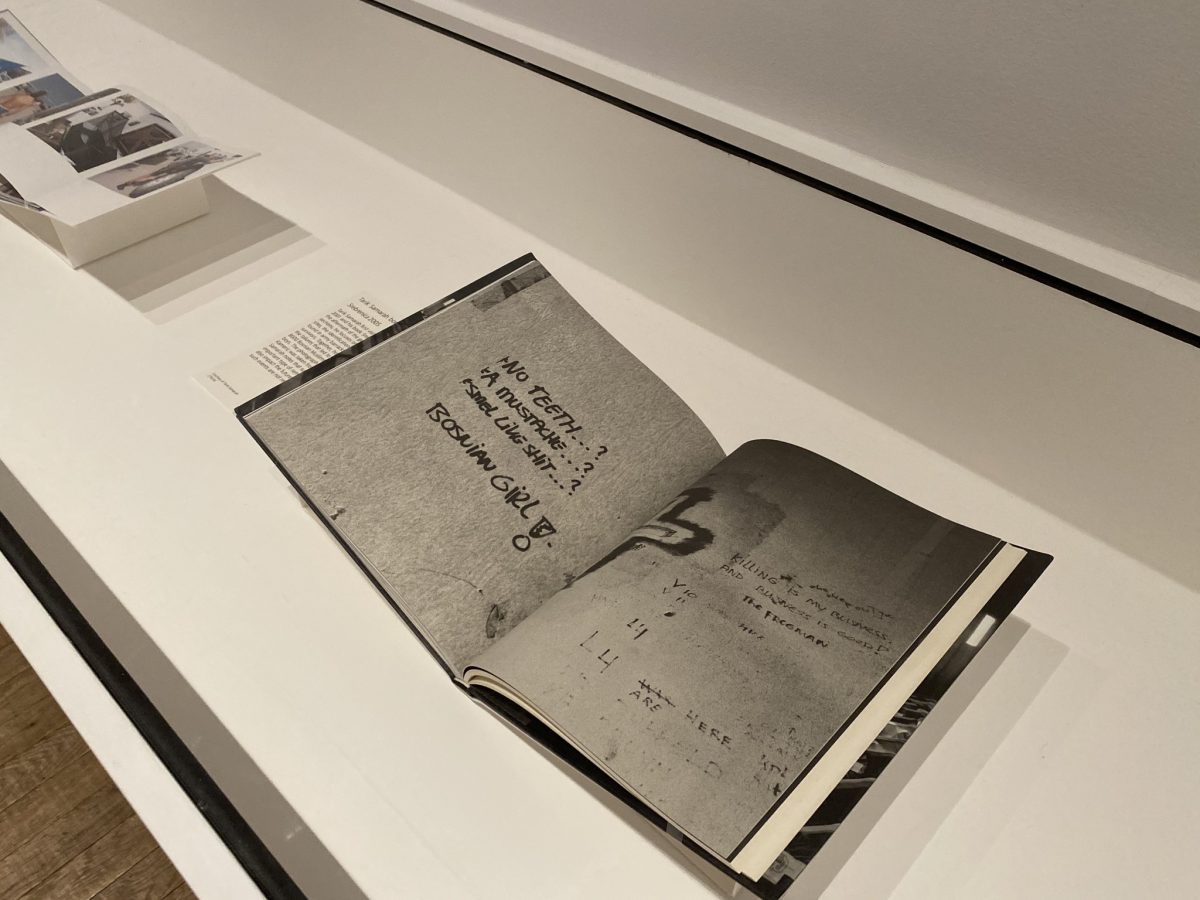

Graffiti written by UN soldiers on the walls of the compound in which they were stationed reveal the prejudices, misconceptions, and dehumanization of the local population. Diversion, inability to empathize, and misunderstanding the victim’s position are part of the narrative that determined the fate of the Srebrenica victims. Photos of the graffiti were recorded, shortly after the war, by Tarik Samarah. They form an integral part of his artistic story about Srebrenica, which is the basis of the permanent exhibition of the Gallery 11/07/95.

Excerpt from the Tate Modern website (“Srebrenica” by Tarik Samarah”)

“Tarik Samarah first visited Srebrenica in 2001 and his book Srebrenica documents the aftermath of the genocide. In different sections, he focuses on the mass grave sites, the identification of bodies, the graffiti found in army barracks and portraits of survivors. Together, his photographs relay the failures that led to the death of over 8000 Bosnian Muslims, mainly men and boys. The photograph of graffiti quoted by Kameric was taken from Samarah’s book. Samarah notes that such images provide an important type of remembrance but should also impact the future too, a way of ensuring such events are not repeated.”

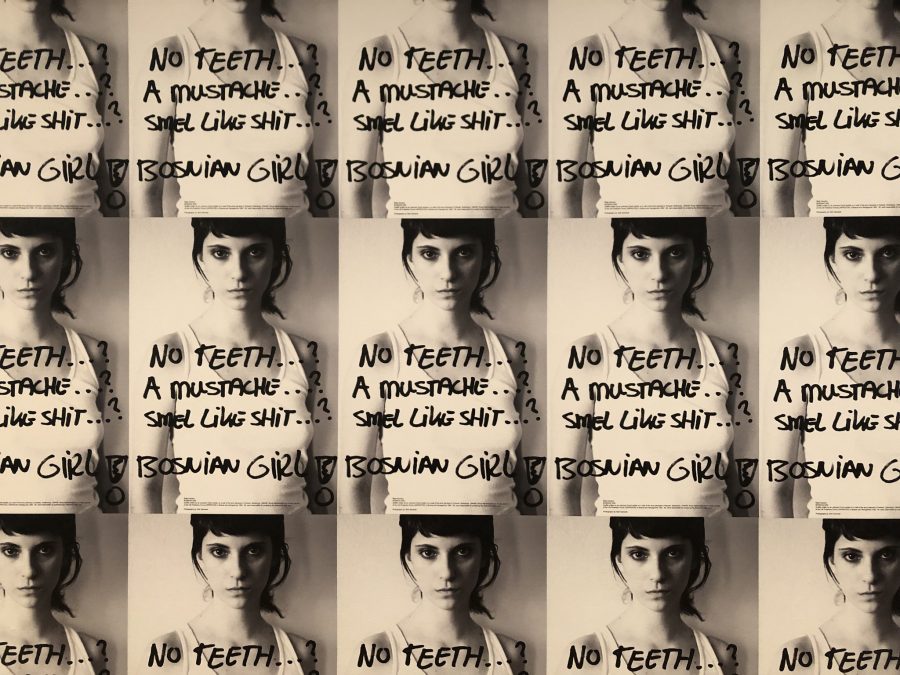

Excerpt from the Tate Modern website (“Bosnian Girl” by Šejla Kamerić)

“In Bosnian Girl artist Šejla Kamerić stares directly at the camera, holding our gaze. The overlaid text quotes graffiti by an unknown Dutch UN soldier found at an army barracks in Srebrenica during the Bosnian war (1992–95). Using the stylised poses found in fashion photography, Kamerić both challenges and embodies the soldier’s words. In this act, she stands for all women who have experienced prejudice because of their gender or identity. She hints at how women become markers of national identity, their bodies politicised as a way to uphold territories and borders. In her gaze, she asks us as viewers to be accountable for our own ways of looking.”